A deep dive into Term Sheets

This article is part of a larger series on Deal Closing. Click here to access all our modules.

💡 A Term sheet is a document that lays out the basic commercials of the proposed investment.

Broadly, the contents of a term sheet can be broken down into:

Round details

Promoter obligations

Investor rights

Other clauses

Now, this is how most blogs about Termsheets begin however, they don’t do justice to completely understand what to do once someone hands a termsheet to you. We want to break down every clause in a document we typically share with founders. You can click here to access our sample term sheet, though we will bring it along with us every step of the way! With that in mind, here is how we would like to structure this conversation:

1. Aligning Timelines ⏰

Investors usually give out the term sheet with an expiry date because they don’t want founders trying to get a better offer from another investor. Once you know which offer to accept, it’s best to sign it promptly.

Signing a term sheet is the first definitive step of a fundraise.

Having said that, it’s important that you take your time to understand the different terms, negotiate them with your lead investor as you see fit, and align on terms. Once everything is agreed upon, your lead investor will send out the final term sheet.

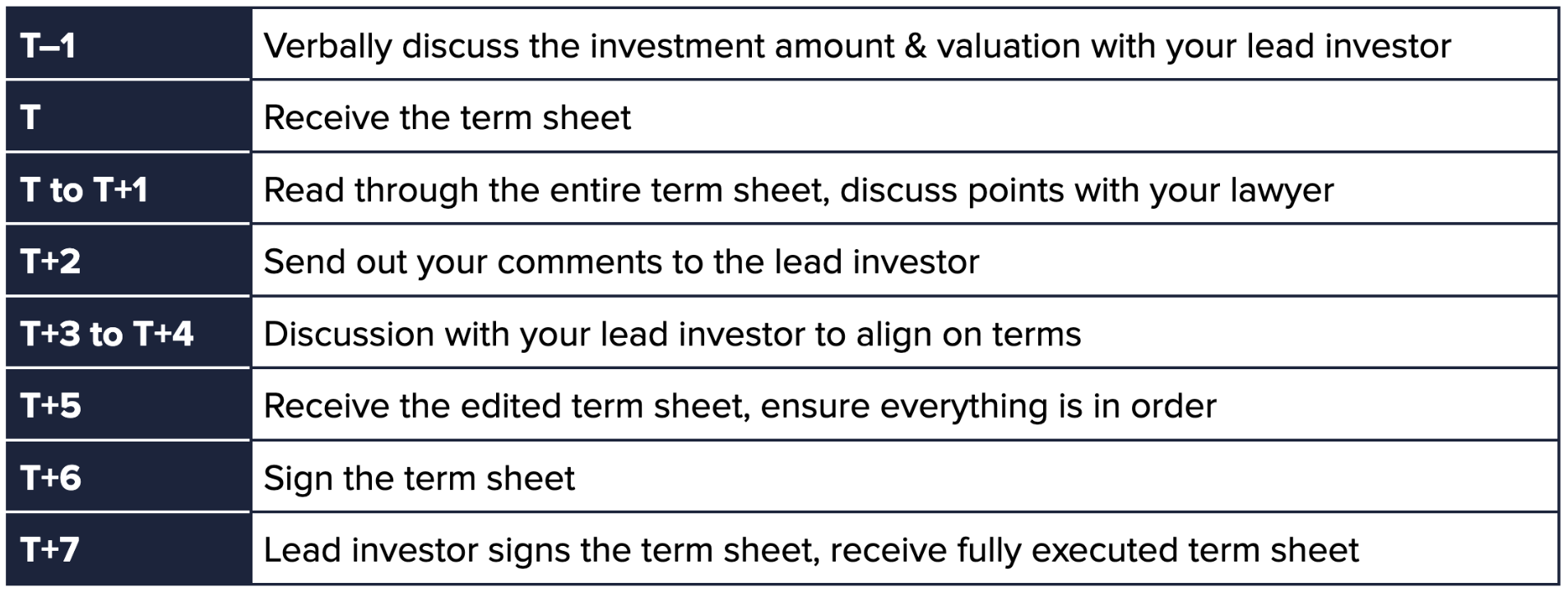

Here’s an indicative timeline of the different steps:

‘T’ being the day you get the term sheet:

The above timeline considers sufficient time for each step but of course you should aim to do it as quickly as possible.

After signing the term sheet, you have the detailed transaction documents, due diligence, regulatory filings, structuring the round construct, and other ad-hoc tasks.

My point being – don’t take more time than is necessary because closing anyway takes time. Try to ensure a prompt turnaround time for each step (not just for term sheet but closing in general).

2. Principal Agreement 🤝

A term sheet is an offer where the investor (usually the largest in the round) lists the different terms that you (the founders) and the company have to agree to.

As you would have observed in the sample term sheet, the terms are not detailed out. It only describes the essence or fundamental understanding of different terms from a business perspective (not a legal one).

The details of the different terms, the mechanism of how they will be followed, the ramifications of dishonoring the agreement – will all be covered in the transaction documents, primarily the Shareholders Agreement (SHA). This is a step after the term sheet.

A term sheet is not technically a legally binding document. However, it carries a lot of weight in that it represents the fundamental agreement between the parties.

🚨 You cannot agree to one thing in the term sheet and ask for another while negotiating SHA. 🚨

Hence, it’s important to understand everything in the term sheet, discuss clearly with your investor where you propose changes to the terms, and sign only if you fully accept what’s written in there. Of course, you might not have everything you want, but our goal is to give you a framework to make the best trade-offs.

3. What each side wants 🍕

First, let’s just zoom out a little bit and understand the different stakeholders and their commercial interests..

Both the investor and founder agree that it takes time to build a startup from scratch. Founders are prepared to dedicate their skill and expertise towards the cause while investors provide the capital required to fund the business. At the end of the day, both of them want the business to be successful. Investors make a good return on their capital investment and the founder makes personal wealth in the process of building a valuable business.

That’s the simple and straightforward bit. Now, let’s get into what’s slightly trickier – the difference in their interests and how it affects the different terms.

Investors place their trust in founders to build the business and responsibly utilize the capital for that purpose. They want to ensure that the founders spend most of their time for a sufficient duration towards building the business. Hence, they’ll put in some restrictions on what the founders can and cannot do, and how they can and cannot use the funds. As a founder, you naturally want to protect against predatory terms which limit the independence and control you need to build the business.

The nature of this business engagement is such that the power dynamic rests with the investors (in most cases!) because it’s the founders who need the money. If you’re a great, credentialed founder, you can choose who to take money from and might get slightly favorable terms but you’d still have to agree to those terms.

4. Breaking down each term 👩🏽🏫

Now, we shall pick up each of the important terms, understand them in sufficient detail, including the perspectives of founders and investors, and their implications on the business, think about how to negotiate and try to arrive at what is usually fair.

To ensure it’s practical, we’ll pick up extracts from the sample term sheet as the basis.

Valuation & investment amount

There are three things here – investment amount, valuation, and type of shares.

There is little doubt that valuation is arguably the most important aspect of an offer. Remember, the term sheet timeline suggested to have a verbal conversation with your lead investor about the amount and valuation. The purpose of that is to align beforehand on the most crucial aspect.

💬 The best investors will try to have this conversation with you and try to work to what’s fair.

How do you discuss valuation?

For a company that has little operating history, valuation is whatever the founder and investor agree it to be. Hence, it’s of little use to discuss the valuation directly. Let’s take an example.

Suppose the lead investor offers to invest $500k in a total round of $600k ($100k for other smaller investors) and offers a post-money valuation of $3mn. Now, as a founder you can directly say that I want a valuation of $4mn. But to be honest, there’s no direct rationale for arriving at either $3mn or $4mn.

💰 The valuation is a derivative of how much capital the company needs and how much ownership the investor wants or the founders are willing to dilute.

Hence, a better way to make a counter-offer is to approach it from that perspective:

Look, $600k at $3mn results in a dilution of 20% which is a bit more than what we’re comfortable with. We don’t want to go over 16% at this stage and our capital requirement is around $550k. So, we believe that we can either do $550-570k at $3.6mn post-money or raise a little less like $520-530k at around $3.4mn.

Deciding the valuation is still fully subjective but structuring it this way helps to make the conversation more rational. The investment amount comes from the use of funds that you’ll have over the next 18-24 months and dilution gives the investor a counter-perspective to think about their intended ownership.

Now, the esoteric question of starting low or high depending on what number you want to end up. Everyone tries to do it and everyone knows so not sure how effective it really is. It’s important to be absolutely clear about what you aren’t willing to budge on. Then, based on your perception of the investor, you can either go in directly with that or try to start with a different number so you eventually settle around what you originally wanted.

When the lead investor gives you a term sheet, they could leave room for other investors or just give you their offer and then it’s up to you if you want to bring in others. This is another reason why you should have a verbal discussion around the round construct with your lead investor on how much space you want to reserve for angels or other smaller funds. It helps in contextualizing the total dilution of the round and a reasonable valuation.

Investors invariably invest in a different class of shares i.e. preference shares because investors want certain rights that founders will not have and hence, holding a different class of shares makes it easier to link the rights to the class of shares held. However, since preference shares generally do not carry voting rights, the investors explicitly call out they’d still have voting rights proportionate to their holding in the company. These terms around CCPS are fairly standard.

Now, let’s discuss the different rights that the lead investor shall ask for. Instead of going in the same sequence as in the term sheet, we’ll try to discuss the points in a sequence such that it makes intuitive sense to understand them (a lot of these are interconnected or dependent on other terms).

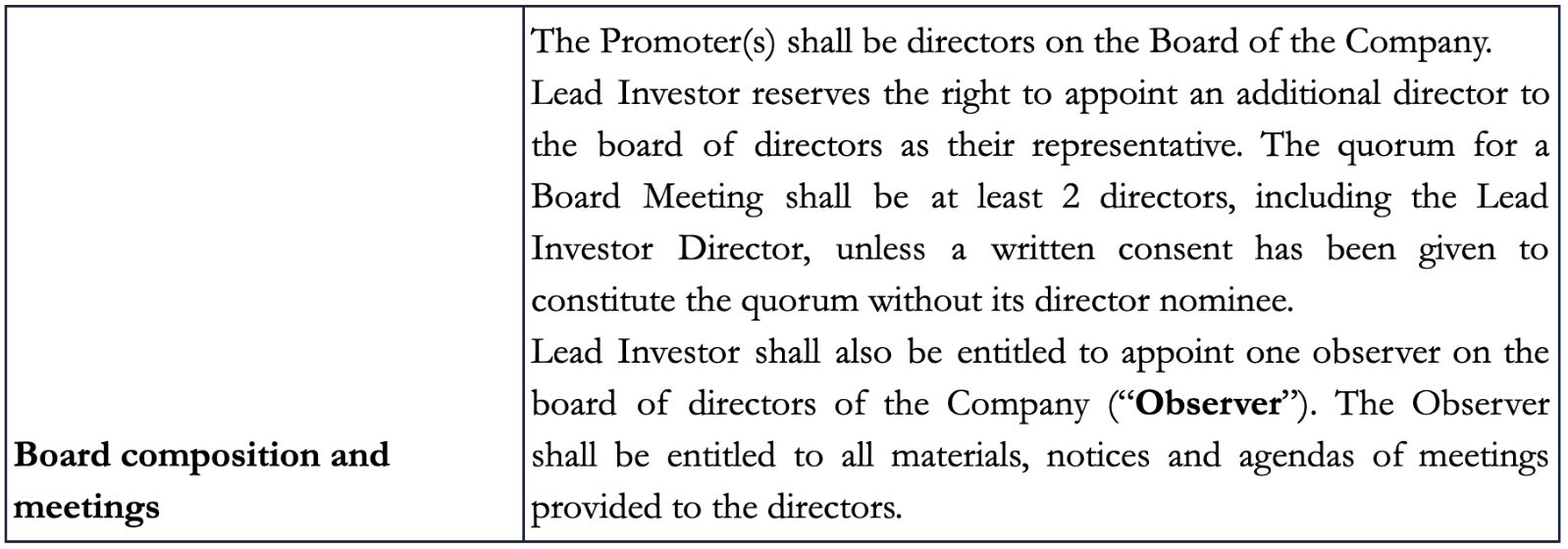

2. Board Seat

The board of directors is the governing body of a company and hence, anyone who is investing a sufficiently large amount of money will want to have a representation to have a say in important matters to preserve their interests. However, practically, at an early stage, there is little difference between the founders and the company and the board of directors. The founders are the company and control the board of directors.

The investor director seat usually comes into play as the company starts to grow and assumes a more formal organizational structure.

It’s likely that your lead investor in the future rounds will also demand a board seat and with each round of financing, the possible size of the board increases. This also means that the founders might have less control over the board as the company grows. So, it’s important to set thresholds for which an investor can have a board seat and to have strong relationships with your earlier investors who can support you as part of the board.

Investor director is non-executive which means that they do not take part in any operations or can make any decisions. However, they might reserve votes on extremely important matters, over which the lead investor will anyway require you to take their approval. On the positive side, a good investor can actually help you with good corporate governance practices.

At an early stage, 1 director seat is usually fair for the lead investor. They ask for an observer seat more from the perspective of preserving some say even in the future when they might have a much lower shareholding. It might be good to have a chat with them about when they intend to actually appoint someone on the board just so you know.

3. Reserved matters or Affirmative vote matters

To be honest, this is the most important part of the entire transaction. Reserved matters is a list of business-related decisions where the founders/company will need to take prior approval from the lead investor. At the term sheet stage, the intent is to agree that the founders will need to ask the lead investor before taking certain decisions.

Since the exact list is not usually discussed at the term sheet stage, each item on this list is up for discussion during the SHA stage.

To still give you an idea, this includes things such as raising your next round, availing debt over a certain limit, business contracts over a certain limit, related party transactions, creating subsidiaries or entering into joint ventures, hiring or firing people above a certain pay scale.

Most of these are critical business decisions that would result in using a substantial amount of the capital that the investors have provided and hence, they’d want to protect against any scope of misappropriation. Honestly, most investors have a standard list of reserved matters and they wouldn’t be willing to remove any of them. However, the scope of threshold for these points can definitely be negotiated.

To make things easier for you, we’ll provide a sample list of these reserved matters when we discuss the SHA part of the closing process.

4. Exit Right

This one is really important because it sets the time horizon for which the investors intend to align their interests with those of the promoters. There are 3 things to unpack here – the time period itself, the exit mechanisms, and the Drag right. So, let’s take them one by one.

First of all, what’s the need for a defined time period?

Most venture funds have a defined life within which they raise money from LPs (limited partners are the people who give money to VCs to invest), invest into companies, make their return i.e. get money back, and then distribute it back to LPs. The total time horizon is usually 7 or 8 years and can be extended to a maximum of 10 years. Hence, investors keep it at 5 years.

The logic here is that 5 years is a sufficient time period to build a business to a scale where investors can get an exit and hence, make a return. Further, the company gets 1 more year after 5 years to facilitate an exit (because operationally it takes time to find a mechanism and to conclude any transaction). It also provides flexibility because when the company raises another round, the exit period will be reset. So, if the next round happens 1 year later and the exit period is reset to 5 years, it becomes 6 years for the first investor.

As a founder, you shouldn’t agree to anything less than 5 years, at the pre-seed or seed stage. Certain investors might also be okay with a 6 year period. But please understand, that whatever the exit period is, investors will usually set a similar time horizon for your share vesting & lock-in (discussed later).

Now, if you read it carefully, the exit clause is worded as if it’s an obligation on the founders to provide an exit (and hence, a return) to the investors. Practically, it is not an obligation, it’s just an imperative requirement in good faith because investors understand that getting an exit depends a lot on external market factors, which might be outside the control of investors. Further, founders are not personally liable to provide an exit to investors.

The different methods of exit i.e. IPO, third party sale, strategic sale, buyback are all methods each of which will have their own process which will be detailed out in the SHA. These are the usual methods by which an investor can get an exit and hence, are listed. It might be worth going through the mechanics of each mode during the SHA stage.

Finally, let’s understand the Drag right, which might sound a little aggressive on the founders. Now, investors rely on the founders to provide an exit for the 5 years + 1 year period. However, they still want an exit in case the founders fail to do so. Practically, this would mean that the company hasn’t been able to raise another round (which gives investors comfort around the future of the business and provides an opportunity to exit) which means the business isn’t doing too well. However, they still want to get an exit because they want whatever money they can get.

In such a scenario, after the 5+1 year period, the lead investor can force all other shareholders (including founders and other investors, if any) to sell their shares, if they find a buyer.

Why force others to sell as well?

Because, if it comes to the point where the lead has to force a sale, it means the business is not doing well and it’s more to salvage some part of the original investment than a successful exit. In such a scenario, the company, the founders or lead investors are on the backfoot vs whoever the buyer will be. Hence, the buyer will determine the terms of the transaction and might want to buy the entire company instead of a minority or even a majority stake. At such a stage, investors don’t want any restriction on their ability to facilitate an exit.

As a founder, is this unfair?

It may be but in all probability, if you’ve spent 5 years building something and it still hasn’t paid off, it might not be such a bad idea to try something else with a fresh start. In fact, in most cases, you’re more likely to shut the company down in 3 or 4 years because you run out of funds, or try for a friendly acquisition, before it really comes to the lead investor exercising the drag right, which is like a last resort.

There’s also a provision of accelerated exit in case of material breach , which is a really serious violation of the SHA. The exact scope of material breach is defined in the SHA and can be negotiated. In principle, it means you did something really unfair and unjust which seriously harms the company’s future and investors’ ability to make returns. In case the lead investor triggers material breach and founders do not rectify it, then the investors can force the founders to provide an immediate exit. In such a fire sale, it’s quite likely that any transaction will occur at a severely discounted price, which means investors will practically sell at a loss.

5. Restriction on Promoter shares and obligations

Now, this one is really important so let’s understand point by point.

🔒 Lock-in period simply means that founders cannot sell their shares for a defined time period. Vesting means that even though founders hold those shares, they will only have ownership to those shares, over time.

At an early stage, investors are practically investing in the founders since there’s not much to the company. In such a scenario, investors want founders’ interests to be completely focused on the company for at least the time period during which investors hold shares. That’s why it’s common for lock-in and vesting for founders to be linked with exit for investors – it aligns the commercial interests of investors with those of the founders.

Now, the lock-in period and vesting schedule can totally be negotiated. However, it’s highly likely that investors would want to anchor these to the exit period. In case the company is evidently further along, you can ask for a shorter vesting timeline. However, most investors would ask for a cliff period (a duration where no vesting occurs) at least for 1 year. The rationale is that after 1 year, the company is likely to raise another round which reduces the probability of making a negative return on investment.

Another important thing to note is that both the lock-in and vesting are likely to be reset at each round.

That’s because whoever the incoming investor is, would want the founders to align their interests from that point on. That’s why it becomes more important to properly present where your company is and based on that, negotiate on this point.

There are a few other nuances to this point, especially what happens to founders' shares in case they leave the company in good faith or bad faith or if they are removed from the company for a justified reason or for an unjust reason. All of these points are detailed out in the SHA and can be discussed at that stage. Just to give a hint – in most of these cases, vested shares can be bought by the company and the unvested are usually transferred to an employee pool.

Now, the non-compete is well understood. The rationale is again, investors depend on the founders so founders leaving the company and starting a competitor leaves the investors hanging. The key point here is that non-compete is valid even if the founder has stepped out from active management but is still a shareholder. As a company progresses, there might be some relaxation in this clause.

Even though the lock-in states that founders cannot sell any shares, they actually can even during the lock-in period. But any sale of shares by founders is subject to ROFR and tag restrictions. Effectively, investors want control over any sale of shares by founders. ROFR basically means that the investors are the first choice buyer for any shares that the founders want to sell. Tag means that in case investors don’t want to buy those shares and founders will sell to an external buyer, then investors can require the founders to sell their shares alongside.

ROFR ensures investors keep their control even if founders sell a little bit. Tag ensures that investors get some liquidity in case founders sell some of their shares.

This gives investors flexibility both ways. As a founder, you can definitely ask for an exception in being able to sell a certain portion of your vested shares without these restrictions for liquidity purposes. How much? It really depends on what your lead investor is okay with.

6. Pre-emptive right

Also referred to as ‘pro-rata’, this basically means that investors can invest in a future round (at the terms of such a round), to maintain their shareholding from the current round. For example, if the lead investors hold 10% after the current round but when the company goes out to raise a next round, the lead investor will be diluted as the company issues new shares to incoming investors. In that case, the lead investor is entitled to buy enough shares to keep their shareholding at 10%.

🛒 This doesn’t mean that lead investors get any discount or favorable terms in the future round – just that they can buy more shares to maintain their shareholding.

Investors want to double down on their winners and from a founders perspective, it’s a good vote of confidence for the incoming investor that the larger investors from the previous round are investing further.

7. Anti-dilution provisons

There are 2 aspects here – one is pure share restructuring in which even though the number of shares change, there is no flow of money. In such a case, the price is adjusted accordingly – simple and fair. The other case is what if a company raises more capital at a price lower than what investors had invested at. The mechanics of anti-dilution are detailed out in the SHA and can be discussed then.

For example, let’s say the investors purchased shares at a price of INR 20k per share. Now, the company raises the next round at the price of INR 15k per share. That’s likely going to happen when the business is in a serious need of capital and hasn’t shown great progress. Now, investors feel they have paid a higher price and hence, want to be compensated for that by getting additional shares.

But from a practical perspective, even though investors hold the anti-dilution right and can choose to exercise it, what really happens in case of a down round is determined only when such a situation arises.

8. Information rights & senior benefits

Investors require the founders to share information about the company’s progress and that’s completely fair. This usually means a management report, operating metrics, financial statements, and other important information. The exact details of what the investors can ask for and the timeline on which the company has to share them is detailed out in the SHA. As a founder, it is good practice to keep your shareholders apprised of the company’s progress while ensuring you spend minimal effort doing that.

Lead investor also asks for the provision of getting or continuing having senior rights in the future. Essentially, as the company grows and many investors come in, there can be conflicts over which investors should hold which rights. By putting this, lead investors try to protect against a diminution of rights in the future. Practically, the rights after each round are discussed during that round and as long as you believe that your investors are reasonable, it shouldn’t be a problem. As a founder, you should also think about what rights different investors should be entitled to.

9. Share transfer by investors

If you recall, when founders want to sell shares, there are plenty of restrictions. But when investors want to sell shares, there are practically no restrictions. That’s because investors are practically holding an illiquid asset which can’t be sold easily. Further, anyone buying shares from an existing investor are likely to see that as a negative and only buy at a discount, in most cases. Hence, investors want the ability to sell their shares freely.

The fair exception to this is the ability to sell to competitors. That applies not just to investors but all shareholders – obviously. The cleanest way to do this is by having a list of competitors in the SHA, which can be updated from time to time.

10. Liquidation preference

This basically means in any event that the company gets liquidated, investors get their money back first, before the promoters.

Liquidation preference is to help investors protect against downside. The rationale here is simple – investors provided the company with the capital and in case the company doesn’t do well, investors should be the first to get their money back. The two options are getting a share of the liquidation amount based on their shareholding or getting the same amount as what they invested. Please note that in neither of these cases can founders be personally liable to provide the required amount to investors.

11. ESOP pool

At an early stage, investors know very well that the founders will have to hire quality talent to build the startup and those early hires need to be given shares as part of the compensation. Now, investors want to protect against dilution (since ESOPs increase outstanding shares but the company doesn’t really get any capital) and hence, ask the founders to create an ESOP pool beforehand.

The percent of ESOP pool is important because you want enough such that it covers enough of the early hires but not so much because it will bring down your shareholding as the founder.

Existing shareholders can definitely be diluted for the subsequent creation of ESOPs. Hence, investors will always push for a higher ESOP such that it at least covers for a couple of rounds of financing. We’ve shared the mechanics of how the creation of the ESOP pool works in our section on the cap table.

12. Conditions precedent

Conditions precedent usually include a number of regulatory filings and few business things that the company needs to do after signing the SHA and SSA but before they can receive the money. Usually, these are quite standard and are listed out in the SSA. However, based on the findings of due diligence, the lead investor might choose to add certain things if they feel necessary. A related thing is conditions subsequent which again includes mostly regulatory filings but can also include few business actions that the company needs to complete after they receive the money but before they can start using it for business.

Please have a good Company Secretary because they’d guide you on how to do it properly.

13. Other miscellaneous terms

Confidentiality because the investment transaction hasn’t happened yet (there’s still a fair bit of time before signing definitive agreements and wiring of money). During this time, it’s best for both the founder and investors to keep this to themselves. Of course, this excludes the professionals who help with the transaction (lawyer, CA, CS, etc.) and other founder friends who you might reach out to get feedback on different terms or guidance in general.

Representations and warranties are basically each party presenting certain basic information about themselves to the other party (for example – we are a valid business concern, we have the ability to enter into this transaction, etc.). Investors also ask for indemnity which is basically protection against any liability that might arise against the company. Further, there might be a few business-related representations (for example – company not having any debt, having the valid government licenses, etc.) which are usually covered as part of Conditions Precedent and Conditions Subsequent.

Investors ask for Exclusivity because they want to ensure that once the founders have signed a term sheet, they aren’t going to talk to other investors about other offers. The timeline of this can be modified but realistically, it takes 60-90 days to complete the transaction, and the investor asks for exclusivity during that time period. To be honest, as a founder, you are free to seek other offers before signing a term sheet, but once you have signed, it’s basically an agreement that you’d go ahead with it, unless something materially adverse and unforeseen happens.

The Lead Investor requires the company to reimburse Expenses (legal, due diligence, costs) incurred related to the transaction. The logic is simple – the lead investor puts the money in the company, so they want it to be used for paying the expenses. It might be worth putting a cap on the amount in the term sheet.

Governing law provides clarity on the basis of rules that will be applicable to the transaction in general (across all documents, compliance) and specific dispute resolution process. If needed, you can request clarity on the latter and it’s detailed out in the SHA.

Alright, so we’ve practically covered all the contents of the term sheet. The appendix might contain additional details, if necessary.

5. Putting down comments 💬

Now that we understand everything, let’s take a look at how to share your points across with the lead investor. You can either do it as bullet points on an email thread or send across redlines on the draft term sheet. But how do you put across your requirements? Well, given how extra we are, we actually made a google doc term sheet with the best way to redline. Click on the button below to access it!

6. Signing ✍🏼

There are 3 parties with respect to the term sheet – the lead investor(s), the company, and the founders. All the founders and one representative each from the lead investor(s) and the company (any one of the founders) sign the term sheet. This can be done physically or through signing software. Usually, the founders sign first and then the lead investor.

And that’s it!

Congratulations, you have completed an important step in your deal-closing journey! Yes, this is only part one of a much longer process but it’s still one box in the green. Follow along in our series as we break down more elements. If you found this helpful, please do share it forward and more importantly tag us on social media if you have found our playbook helpful 🥰